The immune system has safeguarding mechanisms that identify and degrade harmful cells and cellular debris. Patrolling monocytes, a subpopulation of circulating white blood cells, is one type of immune cell serving as such a safeguard and is known to help counteract inflammation leading to atherosclerosis. Now, U.S. researchers have found that patrolling monocytes can also protect against lung tumor metastasis. Their study, entitled “Patrolling Monocytes Control Tumor Metastasis to the Lung” was published recently in Science magazine.

The team used normal and Nr4a1 knockout mice, which do not produce patrolling monocytes, to investigate the role of patrolling monocytes in lung cancer metastasis. “No one had looked at how these cells might function in cancer. The knockout mouse gave us a model to test what they do,” Dr. Richard Hanna, from the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and first author of the paper, said in a press release.

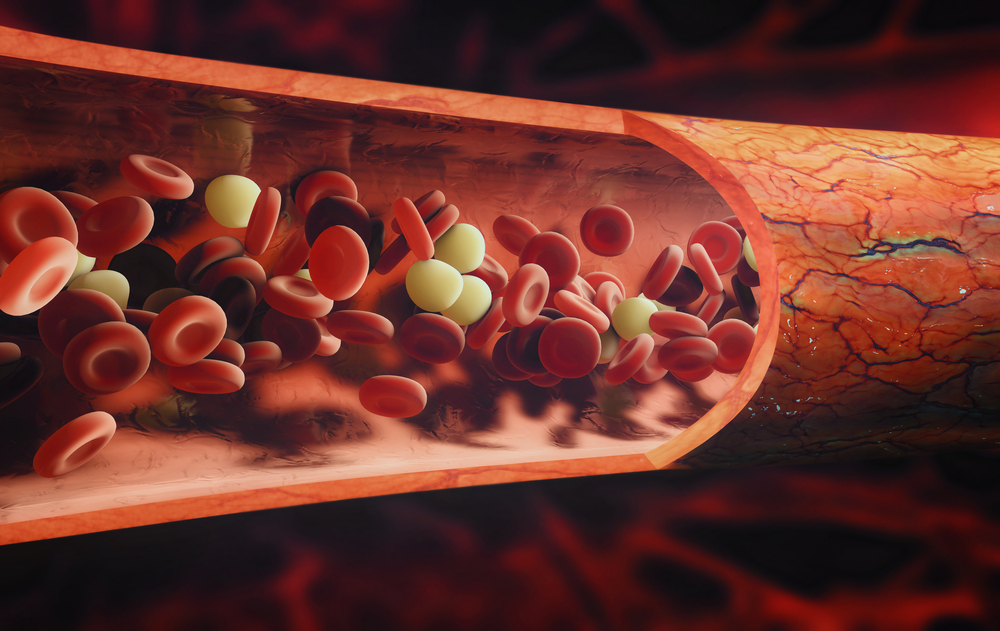

The team injected fluorescent melanoma cells into the blood stream of normal and knockout mice, and tracked the cells’ wanderings in the lung vasculature. After 24 hours, knockout mice vessels had more melanoma cells than those of normal mice. This finding suggests that the absence of patrolling monocytes make animals vulnerable to lung metastasis. To confirm the cancer-protective potential of these cells, researchers isolated patrolling monocytes from normal mice and injected them into knockout mice before infecting them with tumor cells. This procedure blocked the invasion of lung vasculature by melanoma cells.

“The fact that you can add these cells back into a mouse that lacks them and observe reduced metastasis shows that they are key factors in suppressing lung metastasis,” Dr. Hanna said.

However, this protective function was lost when patrolling monocytes were transfused after tumor cells injection, showing that patrolling monocytes can only inhibit lung vasculature invasion by tumor cells before their encounter with vascular cells. The group then fluorescently labeled monocytes and tumor cells and injected them into mice, to visualize in real time their interactions. They found that monocytes pursuit tumor cells and apparently physically block their access to the vascular wall. But authors still are not sure how this exactly happens. Explained Dr. Hanna: “We haven’t proven that patrolling monocytes directly kill tumor cells. What is certain is that the patrolling monocytes recruit other immune cells, called natural killer cells, that are capable of killing tumor cells. Alternatively, these monocytes could scavenge tumor cell debris, which might dampen the inflammatory response.”

Anti-cancer immunotherapy approaches aim at boosting the immune system against particular tumors. This study, showing that patrolling monocytes can block lung metastasis, paves the way for future immunotherapies against this deadly disease. Professor Catherine Hedrick, a scientist involved in the research, believes that the findings could have further applicability: “In this study we saw effects primarily in lung because there are a lot of these types of monocytes normally present in that tissue. Patrolling monocytes may prevent metastasis to other organs as well, a possibility that we will consider in future studies.”