A large international research effort led by principal investigators Richard Houlston and Christopher Amos published new work in Nature Genetics that suggests a link a between BRCA2 and CHEK2 mutations and lung cancer. BRCA2 mutations are most commonly associated with breast and ovarian cancers, but the new findings indicate smokers with BRCA2 mutations are at a 10% higher risk for developing lung cancer than smokers without similar mutations.

A large international research effort led by principal investigators Richard Houlston and Christopher Amos published new work in Nature Genetics that suggests a link a between BRCA2 and CHEK2 mutations and lung cancer. BRCA2 mutations are most commonly associated with breast and ovarian cancers, but the new findings indicate smokers with BRCA2 mutations are at a 10% higher risk for developing lung cancer than smokers without similar mutations.

Already, smokers face a 15% increased risk of lung cancer compared to non-smokers. Carrying BRCA2 mutations increases the risk to 25%. Therefore, a staggering one-quarter of smokers with BRCA2 mutations will be faced with lung cancer at some point in their lives. “Our results show that some smokers with BRCA2 mutations are at an enormous risk of lung cancer,” emphasized Dr. Houlston, from the Institute of Cancer Research in London, in a news article.

The novel findings were made through the 1000 Genomes Project (11,348 lung cancer cases and 15,861 controls of European descent) and additional genotyping analysis (10,246 lung cancer cases and 38,295 controls). There was a large-effect genome-wide association between squamous lung cancer and the rare variant BRCA p.Lys3326X, with an odds ratio of2.47. Additionally, the mutation CHEK2 p.Ile157Thr was found to have a significant odds ratio of 0.38.

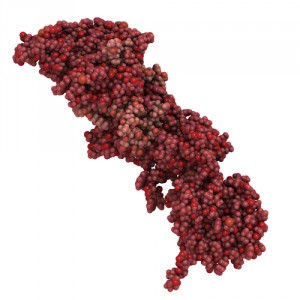

BRCA2 is a tumor suppressor gene, and CHEK2 controls parts of the cell cycle. Mutations in either can allow cancer cell progression and tumor development. Fortunately, drugs such as PARP inhibitors have been successfully implemented in breast and ovarian cancers with BRCA1 mutations, indicating a likelihood of their efficacy for lung cancer treatment. However, it is not yet known if the same drugs will work in lung cancer.

New lung cancer therapeutics would lessen the burden of the disease. More than a million people worldwide die of lung cancer, and it is the leading form of lethal cancer in Britain. As always, there are precautions individuals can take to lessen their chance of developing lung cancer. “We know that the single biggest thing we can do to reduce death rates is to persuade people not to smoke, and our new findings make plain that this is even more critical in people with an underlying genetic risk,” said Dr. Houlston.