A research article published in the new issue of The Annals of the American Thoracic Society by a team of investigators from the COPDGene Study is focused on challenging the accuracy of the current clinical definition of chronic bronchitis (CB). The study’s aim was to better evaluate patients with CB who are at risk for poor clinical outcomes by using a more specific and discerning clinical definition of the disease.

A research article published in the new issue of The Annals of the American Thoracic Society by a team of investigators from the COPDGene Study is focused on challenging the accuracy of the current clinical definition of chronic bronchitis (CB). The study’s aim was to better evaluate patients with CB who are at risk for poor clinical outcomes by using a more specific and discerning clinical definition of the disease.

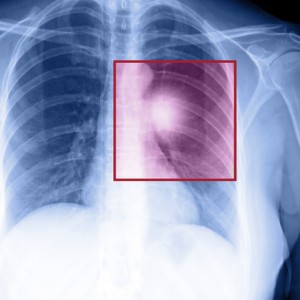

CB is one of two diseases known to cause chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); emphysema is the other. CB is currently defined as a productive cough for three months in each of two successive years, in which there is no other clinical cause. Patients suffering from CB experience routinely irritated and inflamed airways. This causes a thickening of the tissue lining the lungs, with copious amounts of heavy mucous, making it almost impossible for the patient’s lungs to function properly. Patients’ breathing becomes labored and in many end-stage cases, is no longer possible without assistance. COPD affects more than 5% of the population and is associated with a high mortality rate. It is the third leading cause of death in the U.S., where more than 120,000 patients die annually. Smoking and COPD are highly correlated and it is estimated that 9 out 10 COPD deaths could be prevented if patients didn’t smoke.

[adrotate group=”3″]

Victor Kim, MD, the lead author and seasoned researcher in both clinical lung disease management and pulmonary medicine, and his team of collaborators looked at a cohort of patients from the COPDGene study. They assessed whether an alternative definition of CB based on a highly utilized clinical assessment tool known as the St. Georges Respiratory Questionnaire would add any value to healthcare providers ability to successfully evaluate patients at higher risk for poorer disease outcomes. The study assessed many aspects of the disease in relation to its clinical presentation including: specific respiratory symptoms, tissue inflammation, worsening lung function, and the ratio of airway wall thickness. The study concluded that the alternative definition, when used with the standard definition, did add value to healthcare providers ability to properly assess patients at risk for poor clinical outcomes.

There is currently no known cure for CB and the medical community has not yet determined how to reverse the progression of symptoms. With this in mind, what do the results of this study mean for patients with CB or those that may be diagnosed in the future? Should the proposed new definition’s effectiveness in a clinical setting become verified, perhaps healthcare providers armed with a more accurate picture of what the clinical disease looks like will be able to start treatment earlier, and possibly reduce the likelihood of a patient’s progression towards debilitating disease and possible death.