Researchers at UNC School of Medicine in North Carolina recently published in The American Journal of Human Genetics their findings on how specific genetic pathways can influence cystic fibrosis (CF) severity in patients. The study is entitled “Gene Expression in Transformed Lymphocytes Reveals Variation in Endomembrane and HLA Pathways Modifying Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Phenotypes.”

Researchers at UNC School of Medicine in North Carolina recently published in The American Journal of Human Genetics their findings on how specific genetic pathways can influence cystic fibrosis (CF) severity in patients. The study is entitled “Gene Expression in Transformed Lymphocytes Reveals Variation in Endomembrane and HLA Pathways Modifying Cystic Fibrosis Pulmonary Phenotypes.”

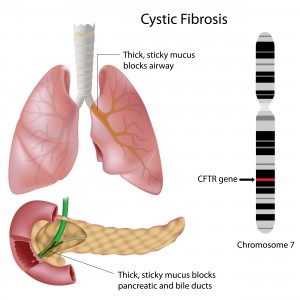

CF is a life-threatening genetic disease in which a defective gene (cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator – CFTR) causes the body to form unusually thick mucus that can result in serious respiratory and gastrointestinal manifestations. Mutations in this single gene are enough to cause CF, although it is thought that disease severity is linked to several other genes and proteins.

There are approximately 1,800 different mutations in the CFTR gene that can cause CF. One of these, a mutation called DF508, was found in around 70% of CF patients and has no approved FDA treatment yet. In a normal situation, the gene encodes the CFTR protein that travels to the cell membrane where it plays a major role in maintaining proper lung function. During this process, the protein can interact with several other proteins and genes. In CF patients, however, the CFTR protein is defective and does not reach the cell surface where it is needed.

By analyzing gene expression data from cells gathered from 750 CF patients in the United States in the last ten years, researchers assessed more than 4,000 pathways and found significant genetic variation between severe and mild CF patients in two particular pathways: the HLA and endomembrane pathways. Endomembrane genes are most likely responsible for the transport of the CFTR DF508-mutant protein to the cell membrane and its proper functioning, while the HLA genes are known to play important roles in the immune system and might be important for protection against pathogens, as is the case of Pseudomonas, the bacteria often responsible for pneumonia in CF patients.

[adrotate group=”3″]

“Right now, there are drugs being developed to fix the function of the CFTR protein that is disrupted in cystic fibrosis, but even then, some patients will respond very well to therapy and some won’t,” said the study’s senior co-author Dr. Michael Knowles in a news release. “Why is that? We think it’s the genetic background – the pathways that we identified contain genes that likely interact with the main CFTR gene mutation.”

The team found that CF patients experience milder symptoms when these genes and pathways are highly expressed, whereas a more severe form of CF was identified in patients where these genes have a lower expression. “Now, we’d like to continue to evaluate the response of patients to new treatments,” added Dr. Knowles. “We want to know if people who respond well have higher expression of these genetic pathways. If so, then we’re really on the heels of personalized approaches to treating CF patients at the level of their genes to lessen the severity of often debilitating symptoms.”

“Now that we’ve found these pathways, we need to dig into the biology to see how specific genes within them influence disease severity. This could help us not only to predict which patients will respond to a given therapy but it may also provide drug targets to lessen the severity of disease for all patients,” concluded the first author of the study Dr. Wanda O’Neal.