Scientists at The Saban Research Institute of Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA), along with co-workers in Mexico and Canada, are targeting a molecule that could play a role in the abnormal growth of cells in pulmonary fibrosis. Called transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β), this molecule may cause lung scarring. Blocking it might prevent the scarring and treat the disease.

Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) refers to a thickening and scarring of the lungs that is caused by unknown factors. The disease results in difficulty breathing and is eventually fatal. Understanding the factors that lead to scarring is critical for developing treatments for IPF.

Increases in TGF-β occur both in IPF and in experimental models of IPF, but the growth factor is also needed for normal immune system functioning. According to Wei Shi, MD, PhD, of the Developmental Biology and Regenerative Medicine research program at CHLA and the Department of Surgery, Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, “This is a very complicated signaling pathway, which promotes mesenchymal stem cell proliferation, while also acting as a tumor suppressant. Our goal was to find a way to target specific cells that result in fibrosis without affecting other cells.”

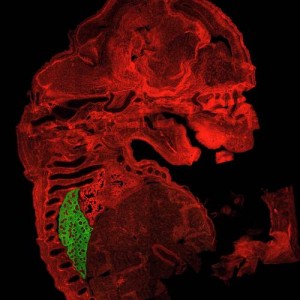

Scientists at The Saban Research Institute developed a mouse in which the gene expression of TGF-β could be turned on and off by the researchers. They changed TGF-β in adult mouse lung mesenchymal cells with various degrees of lung fibrosis. Mesenchymal cells are associated with connective tissue and may be involved in lung fibrosis.

They found that TGF-β could cause fibrosis independently, and that other factors (specifically inflammatory molecules) were not needed for the fibrosis to occur.

[adrotate group=”7″]

They additionally observed that TGF-β affected a gene called P4HA3. This gene may cause collagen to accumulate, which causes fibrosis. It does this by activating prolyl 4-hydroxylase. When the scientists blocked prolyl 4-hydroxylase, TGF-β no longer caused collagen production in both cells grown in a dish and in and mouse pulmonary fibrosis models.

“Our data indicate that increased expression of collagen prolyl hydroxylase is one of the important mechanisms underlying the proliferation of fibrous tissue that is mediated by TGF-β. Inhibiting this enzyme appears to be a promising therapy to interfere with excessive collagen production and deposition in IPF patients,” Shi stated.

The study has identified targets for possible future medications for IPF, and suggests that TGF-β and associated molecules might be candidates. The genetically-manipulated mouse developed by this group may also be used as a research tool in future studies to understand IPF.

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, a California Institute of Regenerative Medicine Training Grant, and the Canadian Institute for Health Research.

For more information, visit CHLA.org or http://researchlablog.org/.