A new study in the Nucleic Acids Research journal has found that different combinations of cis-regulatory elements — DNA stretches that regulate the transcription of nearby genes — contribute to the chromatin structure of the CFTR gene and ultimately to the gene’s varying expression in tissues. Mutations in this gene are the sole cause of cystic fibrosis (CF).

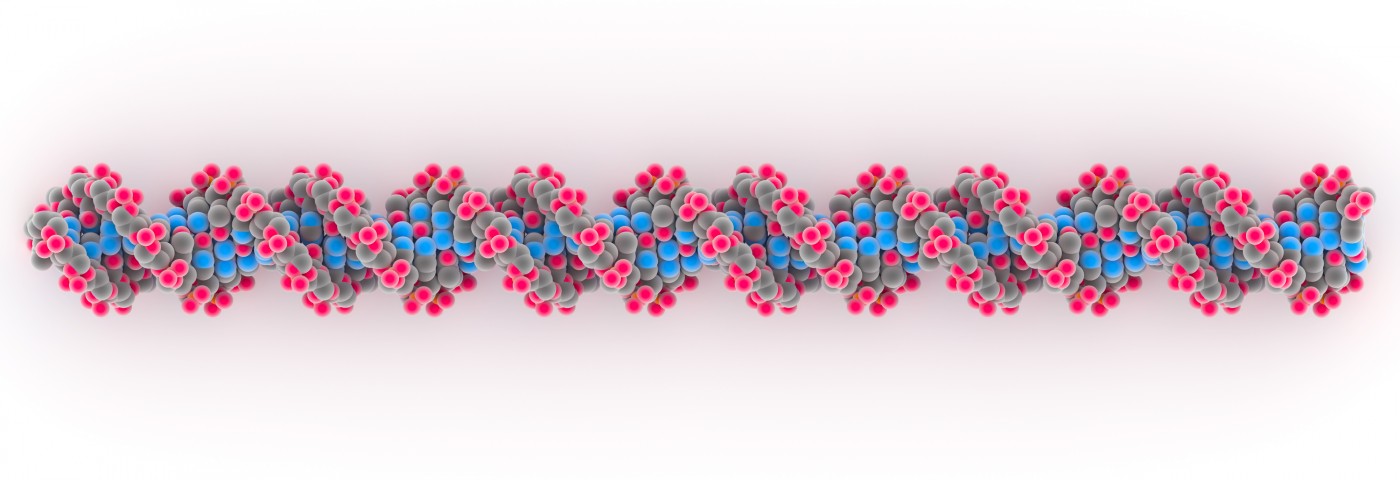

Our genes are present in all cells of the body, and complex molecular factors determine whether a gene is switched on or not — and to what degree the gene product is produced in a specific tissue. The DNA segment harboring a specific gene can, for example, be packed in various ways in different cell types, allowing or hindering transcription. The complex factors behind the regulatory process are not well-understood, and the researchers thought the CFTR gene an apt model for gaining a better understanding into them.

The new study, entitled “Differential contribution of cis-regulatory elements to higher order chromatin structure and expression of the CFTR locus,” set out to investigate how cis-regulatory elements contribute to the expression of CFTR in cells from the lung, bronchi, intestine and male genital duct tract — tissues where the CFTR protein is produced in varying amounts. It was a collaborative effort between Rui Yang and colleagues from Lurie Children’s Research Center in Chicago with Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and Duke University.

The team noticed that while many other genes have tissue-specific regulatory elements, accounting for differing levels of protein production in different tissues, the CFTR gene employs different combinations of cis-acting elements depending on tissue type. These combinations, in turn, engage architectural proteins that fold the chromatin in different ways in the investigated tissues. (Chromatin is a three-dimensional structure composed of proteins and DNA, tightly folded into chromosomes.)

In the tissues expressing the CFTR gene, the team could observe that the chromatin was folded so that the cis-regulatory elements came close to the promoter region — the part of a gene initiating transcription.

When looking the CFTR gene in skin fibroblast cells that do not express the CFTR protein, however, the team noticed that the chromatin was folded in such a way that any interactions between the cis-regulatory elements and the promoter were impossible, effectively shutting transcription off.

The authors believe that their results provide new insights into how other genes are regulated.

In CF, the CFTR gene is expressed mainly in airway epithelial cells, but other organs also produce the CFTR protein. While airway dysfunction in CF is its most apparent symptom, a defect in the production of CFTR protein in other tissues — such as the digestive tract — produces differing symptoms to varying degrees.