A recent study, performed at Stanford University School of Medicine in collaboration with the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center and the California Department of Public Health, reported a new, quick and more reliable diagnostic method for cystic fibrosis (CF), suitable for newborn screening.

The study, “Next-Generation Molecular Testing of Newborn Dried Blood Spots for Cystic Fibrosis,” was published in The Journal of Molecular Diagnostics.

CF, a disease characterized by the accumulation of mucus in organs like the lungs, pancreas, liver, and intestines, is caused by a mutation in a gene called CFTR. To develop CF, a newborn has to inherit two mutated copies of the CFTR gene, one from each parent.

Studies have demonstrated that an early diagnostic of CF in newborns allows for better medical management to reduce symptoms, digestive problems, and delayed growth. “When the disease is caught early, physicians can prevent some of its complications, and keep the patients in better shape longer,”Iris Schrijver, MD, a study co-author and professor of pathology at Stanford, said in a university news release.

Currently, several diagnostic methods of CF are available for newborn screening, a public health requirement in each U.S. state since 2010. However, these diagnostic methods have several limitations.

“The assays in use are time-consuming and don’t test the entire cystic fibrosis gene,” said the study’s senior author, Curt Scharfe, MD, PhD. “They don’t tell the whole story.”

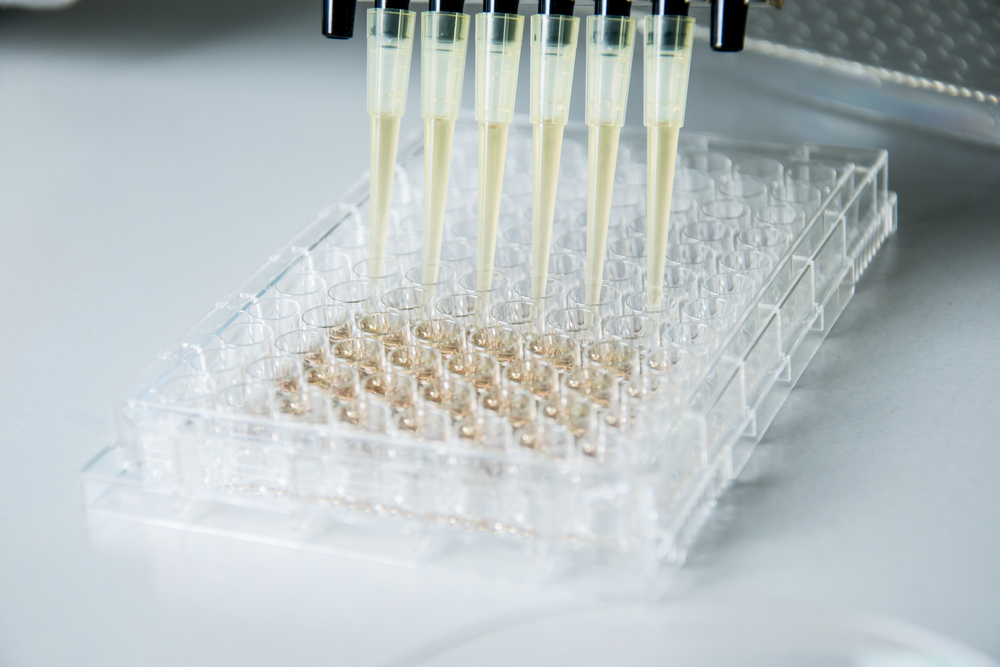

The new method has the advantage of detecting the mutations responsible for CF in one step. It is also cheap and fast, requiring about half the time of current screening methods. Developed by Stanford researchers, it is based on the extraction and development of several copies of the CFTR gene, taken from tiny DNA samples collected from baby’s dried blood spots. The complete CFTR gene is then sequenced.

“In our new assay, we are reading every letter in the book of the CF gene,” Dr. Schrijver said. “Whatever mutations pop up, the technique should be able to identify. It’s a very flexible approach.”

Stanford University is planning to file a patent for the technique. As part of regulatory and quality requirements, new procedures and validation studies will follow to show the method’s reliability of the method. California newborn screening officials will then evaluate the possibility of replacing standard procedures with this method.

“Regardless of how the state decides, the new technique can be widely adopted in different settings,” concluded Dr. Scharfe. “Ultimately, we would like to develop a broader assay to include the most common and most troublesome newborn conditions, and be able to do the screening much faster, more comprehensively and much more cheaply.”

CF is estimated to affect an average of 30,000 people in the United States.