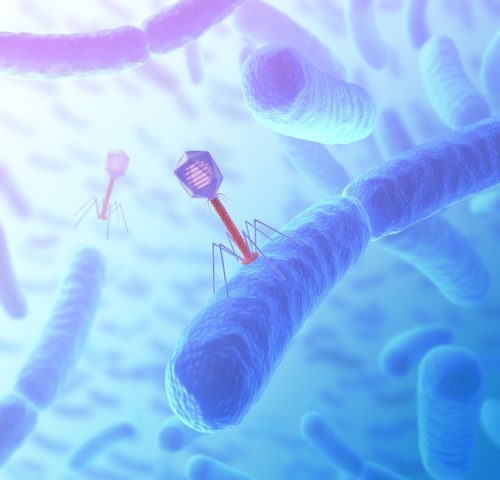

Bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) may help common bacteria better adapt to the lungs of patients with cystic fibrosis (CF), making them more difficult to treat and clear, according to a new study, “Temperate phages both mediate and drive adaptive evolution in pathogen biofilms,” published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The finding has implications regarding the use of antibiotics and a leading author Craig Winstanley, from the University of Liverpool.

The team of scientists from three different U.K. universities grew the bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which usually infects lungs of CF patients, in a substance similar to sputum also found in CF patient lungs. The researchers then infected some of the bacteria with bacteriophages also found in the CF lung.

When researchers analyzed the DNA of the bacteria using genome sequencing, they saw that the bacteria infected with bacteriophages had more mutations which could help them adapt to the lung environment. Some mutations were the result of viral DNA inserted into bacteria genome.

The DNA of P. aeruginosa, directly isolated from patient lungs, was reported to have the same kind of mutations. Because the bacteriophages are commonly found in patient lungs, the researchers concluded that they may play an important role in bacterial adaptation.

“We now know that these bacteriophages can speed up evolution helping bacteria adapt to living in a sputum-like environment,” said Chloe James, a lecturer in medical microbiology at the University of Salford and a study co-author.

Michael Brockhurst of the University of York, the senior author of the study, said more research is needed.

“To design better treatments and preserve our antibiotics, we urgently need to better understand how bacteria evolve in infections,” Brockhurst said.