A new protein called Aiolos, which plays a major role in allowing cancer cells to spread in a wide range of cancer indications such as lung cancer, has been identified by cancer researchers who were also able to determine how the protein works. The new research may lead to using this protein both as a diagnostic tool and in the development of therapeutic drugs to cease or delay spreading cancer cells.

A new protein called Aiolos, which plays a major role in allowing cancer cells to spread in a wide range of cancer indications such as lung cancer, has been identified by cancer researchers who were also able to determine how the protein works. The new research may lead to using this protein both as a diagnostic tool and in the development of therapeutic drugs to cease or delay spreading cancer cells.

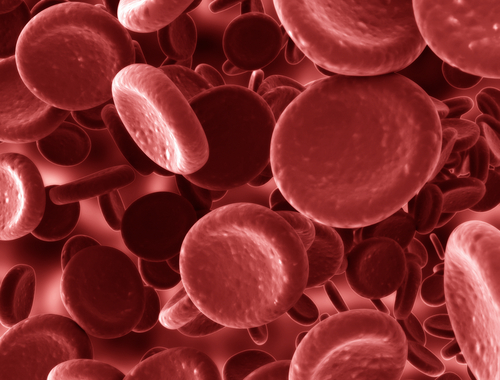

Typical blood cells produce Aiolos, which allows cancer cells to metastasize or spread to other parts of the body by mimicking blood cells’ identity when expressed by cancer cells. Metastatic cancer cells are able to free themselves from tissue, circulating in the bloodstream and forming tumors throughout the body, acting very much like blood cells.

Dr. Lance Terada, Professor of Internal Medicine and Chief of the Division of Pulmonary/Critical Medicine at UT Southwestern, explained that, “This is an important discovery because the metastatic spread of tumors accounts for the vast majority of cancer-related deaths. Now that we know the role of Aiolos, we can look toward therapeutic intervention.”

The study, which is available in online format as well as in the Cancer Cell journal, entitled, “Aiolos Promotes Anchorage Independence by Silencing p66Shc Transcription in Cancer Cells,” discovered that this protein, common in lung cancers, predicts a markedly worse prognosis for lung cancer patients.

Aiolos forms part of transcription factors, a class of proteins known for controlling which genes are turned on or off by binding to DNA, enabling them to promote or block the enzyme that controls the reading, or “transcription,” of genes, making them more or less active.

Aiolos acts by decreasing the production of certain proteins responsible for cell adhesion and thus disrupting cell adhesion processes, including processes that enable cells to grasp to their physical environment, a critically important requirement that allows cells to both survive and spread. This kind of adherence is not essential to metastatic cells. In fact, not having this kind of adhesion allows them to proliferate. P66Shc is another protein repressed by Aiolos. This would restrain the cell’s metastatic ability.

“Despite their importance, cellular behaviors that are largely responsible for cancer mortality are poorly understood,” Dr. Terada explained in a UT Southwestern press release. “Our study reveals a central mechanism by which cancer cells acquire blood cell characteristics to gain metastatic ability and furthers our understanding in this area.”

The research was a co-work between UT Southwestern and Tianjin Medical University, in China. It was led by Dr. Zhe Liu, a former postdoctoral researcher working with Dr. Terada and co-corresponding author on the paper. Dr. John Minna, Professor of Medicine and Pharmacology at the Nancy B. and Jake L. Hamon Center for Therapeutic Oncology Research, and Dr. Luc Girard, Assistant Professor of Pharmacology were other UT Southwestern researchers involved.

The research was funded by the Ministry of Science and Technology of China, the National Natural Science Foundation of China, the Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Commission, the specialized Fund for Doctoral Program of Higher Education, the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation, the James M. Collins for Biomedical Research, and the National Institutes of Health.